Completed by 1820, the DeButts’ 5 bay brick mansion became the home of Virginia statesman John Armistead Carter and his son, cavalry commander Richard Welby Carter. The legacy of this estate was made during the antebellum years and the Civil War, but it endures in communities across the Virginia Piedmont Heritage Area, including the historically black villages of St. Louis and Willisville.

The property now called Crednal, and long associated with the Carter family, has its beginnings in the 18th century as a tenant farm owned by Benjamin Tasker Dulany, Jr. Like many tracts in southwestern Loudoun, it was leased to a farmer who improved the plot using forced labor. By 1785 about a dozen enslaved workers were at the property, owned and overseen by a white man living in a small, one and a half story stone residence. A generation later, Richard Welby DeButts and his wife Louisa Dulany expanded the residence to the brick edifice we see today. A sizable and well-furnished home on some 1,000 acres, a wealthy Tidewater visitor rather dismissively described it as ‘a small brick home with a yard’ when he came to the area in 1866.

Richard Welby died a few years into his marriage to Louisa Dulany, who then lived in the home with her second husband, Edward Hall, and their children from both marriages. Richardetta DeButts, daughter of Louisa and Richard, married Virginia statesman and Fauquier resident John Armistead Carter in 1834. They probably moved into the home around 1845, and the estate was likely named ‘Crednal’ during this time. The name is an homage to the Carter roots in Credenhill, Herefordshire, England. John Armistead Carter is perhaps best known as one of Loudoun’s two delegates to the 1861 Virginia Secession Convention in Richmond, alongside Convention President and Leesburg resident, John Janney. Carter was steadfast in his refusal to vote for secession. A lawyer and former member of the state legislature, Carter believed that states did not have the authority to secede from the union. Still, as a Virginia native and an enslaver, Carter supported the Confederate cause during the Civil War.

Carter’s VMI graduate son, Richard Welby Carter, organized a cavalry company in Spring 1861, which became Company H of the 1st VA Cavalry. The young Carter was already an accomplished horseman, having won a number of the prizes at his cousin R H Dulany’s inaugural Union Colt & Horse Show in 1853 (later renamed the Upperville Colt & Horse Show.) Carter served throughout the war, having a horse shot out from under him, being imprisoned multiple times, and rising to the rank of Colonel. Crednal itself saw action during the war, notably during 1862’s Battle of Unison, and 1863’s Battles of Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville. The Civil War’s most lasting scars are evidenced by what we don’t see at Crednal. In December 1864 General Wesley Merritt’s infamous Burning Raid claimed mills, barns, stables, corn cribs, and fields across Loudoun Valley. Determined to smoke out Mosby’s Rangers and destroy the livelihood and morale of the residents, the raid is most likely responsible for the destruction of the antebellum outbuildings.

There are, however, other important hallmarks of Crednal’s past and its dissolution as a plantation following the Civil War. In 1860, John Armistead Carter is listed as owning 26 enslaved people at Crednal, most of whom were probably field hands. Together with the enslaved populations of nearby Welbourne and Catesby, about 100 people lived in bondage in the immediate area. These families were as intertwined as the Dulanys, Carters, and DeButts were. They knew the landscape, they survived the clash of warring nations, and on the other side of war they began to build anew.

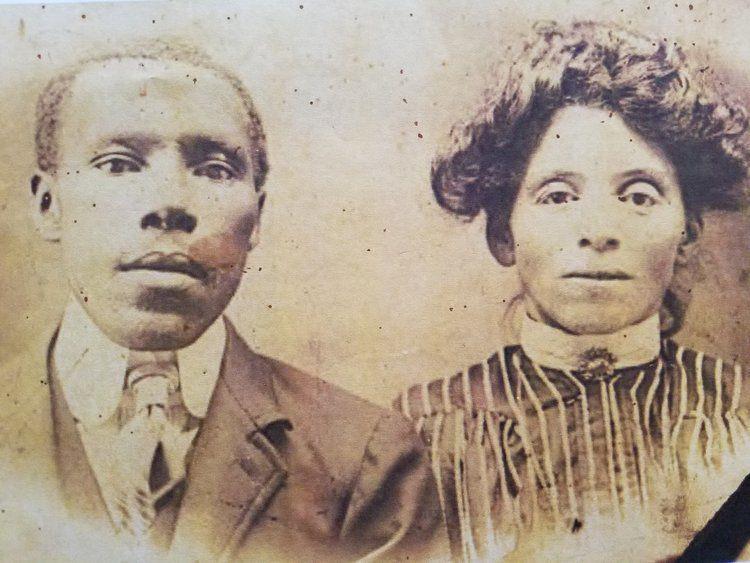

The Jackson and Evans families bought small acreage to the west of Crednal alongside Henson and Lucinda Willis, ‘near Clifton.’ The community, which named itself Willisville, asked John Armistead Carter for support to build the 1868 schoolhouse. George Evans was the village’s first pastor. His wife Julia was likely born at Crednal and was buried there as well. While she was born into slavery, she was buried a free woman. Hers is the only carved headstone in the enslaved cemetery. To the east of Crednal, St. Louis boasted 14 families, many formerly living in slave quarters on nearby plantations. Though modest, these villages show the prosperity and opportunity of postwar life. Both Willisville and St. Louis are active communities to this day and are well worth a visit.

One thought on “Crednal, “a small brick house with a yard””