Eleanor Truax was born in 1869 to US Army Captain Sewall Truax, a Civil War Union veteran, and Sarah Chandler Truax, both born Canadians, but raised as New Englanders. After the Civil War, Major and Mrs. Truax were stationed at Fort Lapwai in the Idaho Territory with the US Army, preventing prospective miners from invading the Nez Perce Reservation during the 1860s gold rush. Major Truax ran a general store on the Reservation prior to the family’s departure for his next post, facilitating the building of a road through the Lolo Pass, a former Nez Perce trail crossed by Lewis and Clark in 1805. Eleanor Truax grew up in the wild northwest, among the rough and tumble manifest destiny of frontier culture, neighboring with Native Americans, prospectors, career soldiers, and rugged terrain.

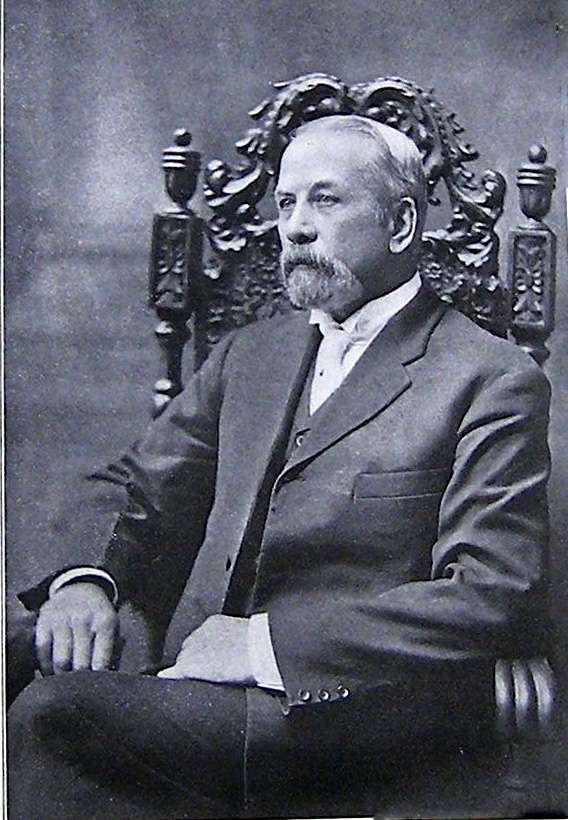

Eleanor Truax became a teacher in Spokane, Washington, where she married and was widowed very suddenly at a young age. Mining stock from her late husband gave Eleanor financial security, which allowed her to grieve in Europe, studying foreign languages, music, and culture until the onset of the Spanish-American War brought the family back to Walla Walla, Washington. There she met Captain Floyd Harris who was training troops preparing to depart for the Philippines, before embarking himself to join General Arthur MacArthur as an aide-de-camp. They started writing each other and later married in Hong Kong in 1900.

In the early years of their marriage the Harrises raised their children in Manila, England’s Lake District, and Vienna, where Col. Harris served at the court of Emperor Franz Joseph. Mrs. Harris joined the Royal Horticultural Society of London and fell in love with England’s narcissus, or daffodil, relating to the Lake Poets, especially Wordsworth who canonized the flower with his 1815 “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud.”

And then my heart with pleasure fills, And dances with the daffodils.

William Wordsworth (1815)

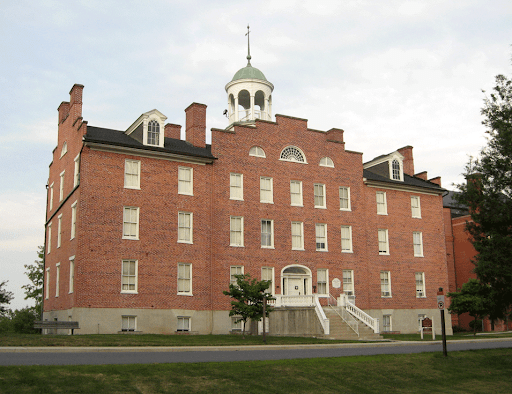

In 1907, the Harrises returned to America in search of an inspiring weekend retreat, which they found in Aldie at Stoke. Mrs. Harris immediately upon seeing Stoke, stated “This is home.”

It became more than just a weekend home. She went straight to work transforming the grounds into terraced gardens with hedges of boxwood and rows of daffodils, breathing European flair into this historic Virginia farm, formerly owned by the Berkeley family of longstanding Virginia pedigree. Eleanor worked with Beaux Arts architect Nathan Wyeth to renovate and expand the 1840 Greek Revival home into a Renaissance Revival estate. Nathan Wyeth later would design a bevy of the Embassy buildings and official residences in Washington, D.C., in addition to the D.C. Armory, and the West Wing of the White House. They together accomplished a simpatico blending of the two eras of Stoke into such a stunning masterpiece which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2015. In addition to its architectural design, the register accepted the nomination because of the legacy of Eleanor Truax Harris and her contributions to horticulture.

Eleanor Harris created the Berkeley Nurseries at Stoke, which became the Narcissus Test Gardens for the Garden Club of Virginia. She nurtured and hybridized daffodils and as the Garden Club of Virginia’s publication Garden Gossip stated, she introduced daffodils to the general Virginia gardener who may previously have given them little notice. Mrs. Harris predicted Holland bulbs would be embargoed by the United States in 1925 due to Dutch Elm Disease, and she arranged large shipments of bulbs to beautify the village of Aldie and its surrounding homes with daffodils. Mrs. Harris founded the Aldie Horticultural Society in 1923 with her group of fellow gardeners who also planted the imported bulbs, giving them the nickname of the “Aldie Bulb Growers.” This later enabled Aldie families struggling financially during the 1930s to make money selling cut flowers that were taken by train from The Plains, Virginia to New York City. Women seldom could assist in providing income in upper-class homes, due to social mores and tradition, but in this instance, Mrs. Harris provided an outlet for women to engage in industry without undue judgment. Her boxwood cuttings also made their impact on the surrounding countryside. The Garden Club of Virginia noted in 1937 that: “The renaissance in box was largely due to Mrs. Harris. She loved this beautiful evergreen and grew acres of different varieties with extraordinary success.”

At her passing in 1937, editor Douglas Southall Freeman wrote of Mrs. Harris in the Richmond News Leader

“The gracious obituary of Mrs. Eleanor Truax Harris we had the pleasure of printing Saturday did not overstate the services of one of Virginia’s best citizens…. Her home, Stoke, at Aldie, not only is one of the most beautiful places in Virginia but also was the seat of a hospitality and a kindly culture that enriched thousands.”

Richmond News Leader, April 9, 1937

Eleanor Truax Harris was the spouse of a well-regarded statesman with an accomplished career, but she established her own fame and legacy. A generous, community-minded woman, Mrs. Harris brought a quintessentially American strength and toughness mixed with a sophisticated European sensibility to Aldie. She was the perfect match to Col. Harris, and was equally comfortable in the high courts of Europe and the hills of Virginia. Her flair, vision for improvement and beautification all speak to Mrs. Harris’ artistic character; the daffodil imprimatur she left blooming in her beloved village speaks to her continuing presence and legacy.