Within the larger scope of the American Civil War, October 21 1861’s battle at Ball’s Bluff near Leesburg, Virginia, is hardly a footnote. Often summed up as a scouting mission gone awry, the dramatic fight along the banks of the Potomac nevertheless loomed large in United States culture and politics.

One of the clearest effects of the battle was the formation of the Joint Committee of the Conduct of the War, formed on December 9, 1861. In the intervening weeks since the battle, Northern newspapers and politicians clamored that the decided defeat at Ball’s Bluff must be the fault of someone, rather than a sum of problems including lack of information, too few resources to move troops across the Potomac, and poor communication. Radical Republican Senators Benjamin Wade and Zachariah Chandler formed the Joint Committee to investigate the defeat at Ball’s Bluff, but the ‘investigation’ quickly determined that Brigadier General Charles Pomeroy Stone would be the battle’s scapegoat. Stone was an ideal target. His aristocratic manners made him distant from otherwise loyal soldiers and he was a West Pointer with relatively few political friends. Even better, accusing Stone of gross disloyalty would also absolve the rash decisions and poor leadership of Col. Edward Baker, a well-liked politician and the only sitting U.S. Senator to die in combat.

Stone was arrested shortly after midnight on February 9, 1862, though he was not told of the charges against him. The Brigadier General was imprisoned for seven months without trial or court marshal, and though he was eventually released and restored to the Army, his reputation was never the same. Charles Stone was the Committee on the Conduct of War’s first casualty, he was by no means its last.

During the weeks and months after the Battle of Balls Bluff, the encounter was discussed publicly in art and literature. It seems odd that a minor engagement would capture the Northern zeitgeist, but its occurrence right at the end of the campaign season (and the lack of subsequent action) gave the public little else to chew on through the winter. There is also something hauntingly compelling about the scene of cornered United States troops being forced off the high ground and into the cold dark waters of the Potomac. Dozens of soldiers drowned that night, and their bodies were pulled from the river days and weeks later at places like Great Falls and in Washington D.C. itself.

One unfortunate 2nd Lieutenant of the 15th Mass., John William “Willie” Grout, was shot while swimming to the Maryland shore. His body was pulled from the river two weeks later and was only identified by the name stitched into his clothing. Henry S. Washburn wrote a poem, “The Vacant Chair”, about Willie, and the words were set to music and quickly became a Civil War standard.

Colonel Baker’s death also became a point of fascination. The four shots to his heart and brain and the scramble to save his body from the grabbing Confederates inspired artists and poets. In fact, 10 year-old Willie Lincoln submitted a poem, “Lines on the Death of Colonel Baker” to the National Republican.

H. Wright Smith after drawing by F.O.C. Darley (Library of Congress)

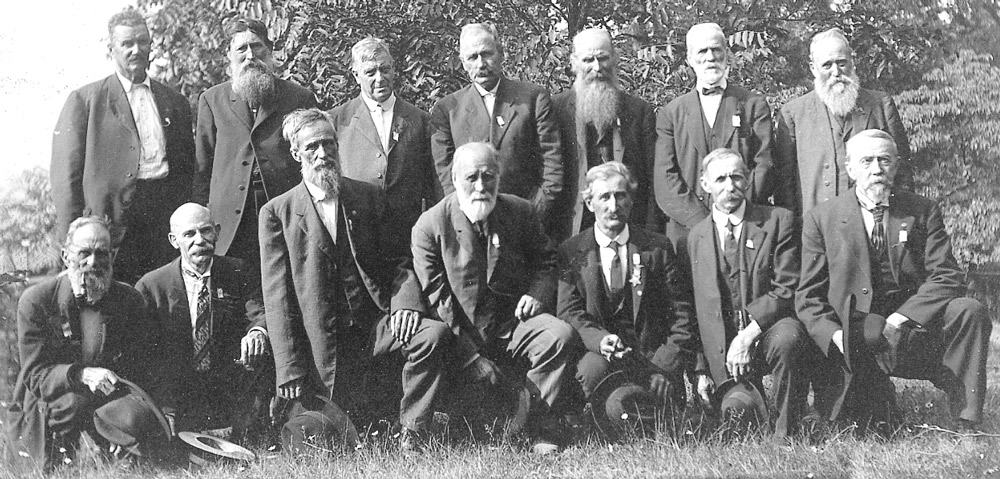

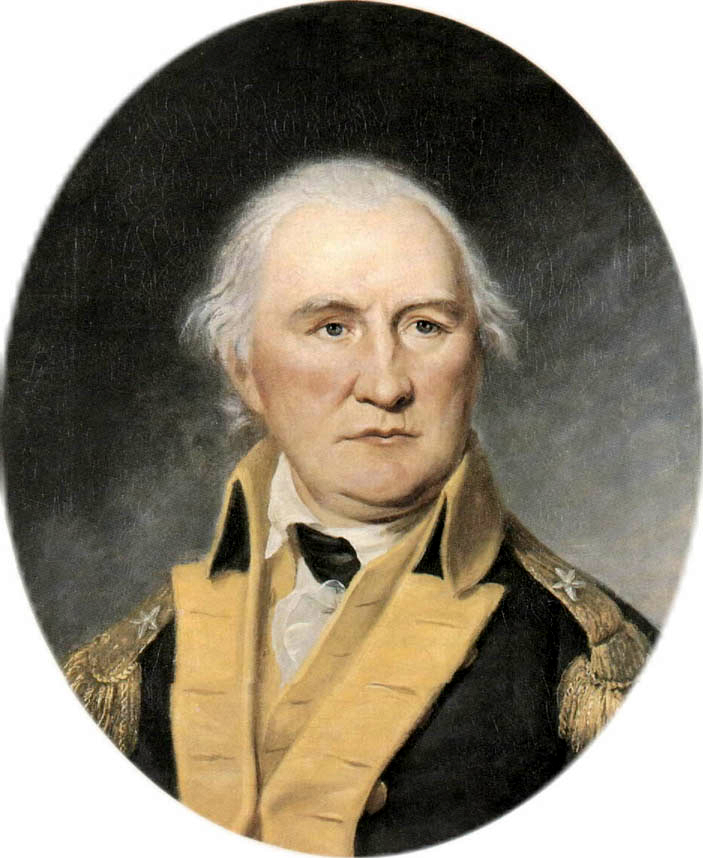

The longest reach of the Battle of Ball’s Bluff can be found through the lives of its survivors. Many United States soldiers engaged in the fight were on the battlefield for the first time, including 20 year-old Lt. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. of the 20th Mass., the “Harvard Regiment”. During a fierce exchange with the Virginians and Mississippians, Holmes was shot almost completely through the chest. The bullet was removed and Holmes went on to fight in significant battles including Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania Courthouse. Holmes and others felt that they had discovered their duty in war, and that their service was at once heroic, horrific, and vital for the preservation of the Union. Even years later the mindset held true. In an 1895 address at Harvard affirmed the nobility of the idea of war, “For high and dangerous action teaches us to believe as right beyond dispute things for which our doubting minds are slow to find words of proof.” Oliver Wendell Holmes would take this outlook and dedication to philosophy to the Supreme Court, where he sat as an Associate Justice from 1902 to 1932. (Learn more about Holmes on November 21 with author Stephen Budiansky)

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. the soldier

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. the Justice

For many years the battlefield at Ball’s Bluff was confined to 76 acres and the 3rd smallest National Cemetery in the nation. An expansion of the battlefield was approved in 2017, confirming over 3,000 acres in Loudoun County and across the Potomac as historically significant. As part of the Mosby Heritage Area, Ball’s Bluff occupies not just physical space in our beautiful landscape, but also serves as a reminder of the small battle that disproportionately captured the attention of a Nation.

Class Activity: In your own words, please answer the following questions

- After the United States lost the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, who became its scapegoat? Why?

- Examine the image above, “Federal soldiers driven into the river.” What made the battle of Ball’s Bluff so horrible for United States troops and their families?

- How do you think the Civil War affected young Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.?