When we study history the vast majority of what we learn comes from written documents. Letters, diaries, census records, church and government records – all of these are essential for piecing together the past. What do we do when there aren’t any written records, though? What about groups that were largely illiterate in the past? One of the best ways to place them into our historical narrative is through archaeology, because everyone might not leave a written record, but everyone leaves material evidence and impacts the historic landscape. This is particularly important for studying the Native groups that inhabited the Heritage Area before European contact.

Broadly speaking, pre-contact Native history is divided into three periods. The earliest, known as the Paleoindian period, began around 16000 BC and continued up to around 8000 BC. This represents the earliest human habitation in the Virginia Piedmont, and some of the most important discoveries about this era were made right here in the Heritage Area. As the landscape and climate changed, the Paleoindian period gave way to the Archaic Period (ca. 8000 BC-1000BC). This was a time of transition, as retreating glaciers and gradual warming allowed Native people to settle into a semi-nomadic lifestyle. Limited agriculture and fishing began to augment traditional hunter-gatherer sustenance. Societies became more complex as people began living together in larger groups, and wide-ranging trade networks formed.

Around 1000 BC the Archaic Period gave way to the Woodland Period, the final period of pre-contact Native civilization in Virginia. The creation of pottery, widespread adoption of agriculture, trade networks stretching thousands of miles, and increasingly elaborate social and cultural hierarchies appeared during this period. In many ways, this is the Native Virginia that exists in the imagination today. Larger villages were established, sometimes bound together as tributaries to a powerful local ruler. The “three sisters” agriculture of corn, beans, and squash, grown in areas cleared for planting by handmade stone tools. Hunters abandoning spears for the bow and arrow. This is the Native landscape encountered by John Smith during his early visit to the Chesapeake, and it would be recorded by European explorers and settlers during the 16th and 17th centuries. Almost everything we know about the Woodland Period in the northern Piedmont, however, comes from carefully conducted archaeological excavations. The Natives of the area left no written record, and by the time Europeans arrived in the modern Heritage Area, the original cultural groups had largely been displaced or dispersed by warfare and migration and decimated by disease. To get a glimpse at what this area would have looked like in the Woodland Period, let’s turn to the archaeological record.

During the Late Wodland Period (900-1650 AD) the northern Virginia Piedmont was occupied by a number of different groups that archaeologists differentiate by the types of pottery and tools they made, their settlement patterns, burial customs, and so on. The three most significant in the modern Heritage Area were the Montgomery Complex, Mason Island Complex, and Luray Complex. These groups overlapped in both time and space, occupying the middle Potomac Valley and surrounding areas from around 900 AD to 1400 AD. Although there were many distinctions between these groups, they did share many common cultural traits. They all used similar styles of projectile points for hunting and war, made from locally procured chert, quartz, and rhyolite. Although the materials for making their pottery varied, they were similar in shape and shared common decorations made from impressing cordage into the wet clay. In addition to pottery and stone tools, archaeologists have also recovered decorative beads made from shells and bone, as well as personal items like tobacco pipes. The locations of their villages varied by culture, but they consisted of wood and bark wigwams built in oval shapes, sometimes surrounded by wooden palisades for protection.

These cultural complexes dominated the region for several centuries, but around 1450 their presence began to wane. Some sort of cultural upheaval caused these people to migrate further east, into the tidewater region. Some archaeologists speculate that the growth of powerful nations to the north and west, including the Iroquoian people, pushed them from the Piedmont and Valleys. Settling along the tributaries of the Chesapeake, the former Piedmont inhabitants were likely the ancestors of the groups encountered by early colonists in the 17th century.

In a piece of historical irony one of those groups, the Piscataway, would return to the Piedmont by the end of the 17th century. Weakened by disease and pushed west by European settlement, some of the Piscataway left southern Maryland and settled temporarily on Heater’s Island, near Point of Rocks. In 1699 they were visited by Giles Vandercastle and Burr Harrison in the first recorded European/Native interaction in Loudoun County. They later gave an eyewitness account of the Piscataway fort on the island.

…we came to ye forte or Island. As for the number of Indeens, there was att the fforte about twenty men & aboute twenty women and about Thirty Children, & we mett fore. We understand theire is in the Inhabitance a bout fixteene. They informed us there was fume outt a hunting, butt we Judge by theire Cabbins theire cannot be above Eighty or ninety bowmen in all…

Six years after their visit from Harrison and Vandercastle, the Piscataway at Heater’s Island were struck by illness. Their numbers were so reduced that by 1712 they had abandoned their settlement there and moved north to join other refugee groups driven from the tidewater.

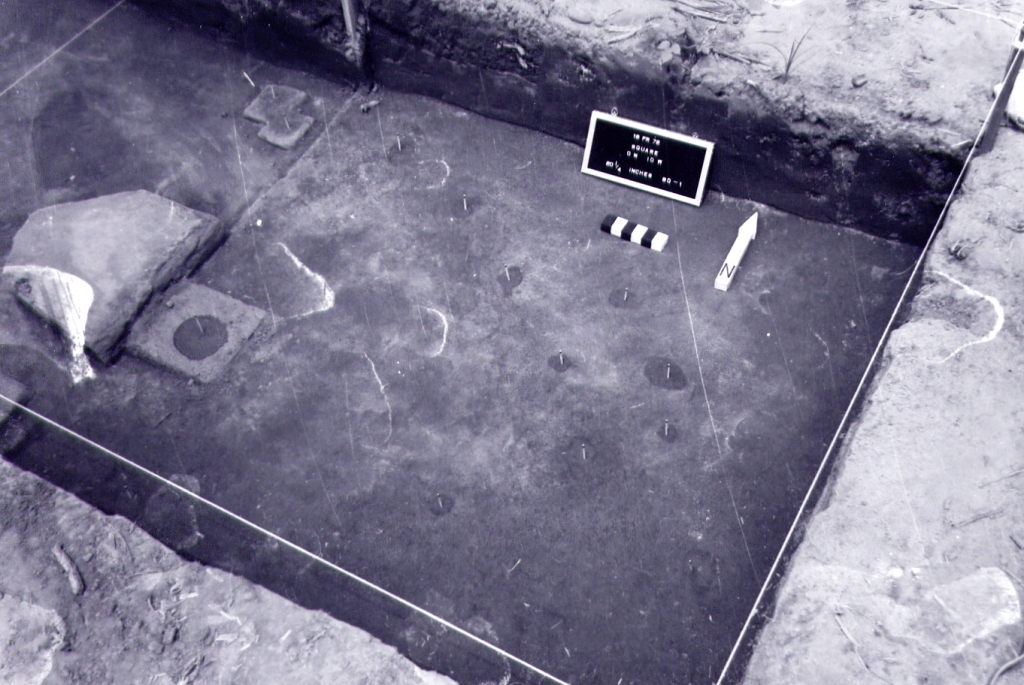

With so little written evidence, the archaeological evidence is crucial to learning about these people. Archaeological excavations are a painstaking process, requiring an exacting level of detail ad meticulous record keeping. The recovery of the artifacts themselves is important, but even more so is recording the exact context that they are discovered in. The relationship of artifacts to each other and to features on the site, like post holes or storage pits, allows archaeologists to piece together how these people lived and interacted with the landscape. Removing artifacts without recording this information destroys the ability to learn more from them, and potentially damages important features as well. Although the evidence is below our feet, preserving our archaeological heritage is just as important as the buildings and battlefields we fight to protect above ground. If you want to learn more and participate in archaeological work in a way that protects these resources, we encourage you to reach out to your local chapter of the Archaeological Society of Virginia.

Recommended Reading

Potter, Stephen Commoners, Tribute and Chiefs: The Development of Algonquian Culture in the Potomac Valley. University of Virginia Press. 1993.

Rice, James Nature and History in the Potomac Country: From Hunter-Gatherers to the Age of Jefferson. Johns Hopkins University Press. 2016.

Means, B. K. Late Woodland Period (AD 900–1650). (2014, May 30). In Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved from http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Late_Woodland_Period_AD_900-1650.