It started with a feud in the paper and two Masters of Foxhounds from Massachusetts. Harry Worcester Smith, MFH Grafton Hunt, wrote in Rider and Driver that the American foxhound should be a recognized breed, separate from British bred foxhounds. Meanwhile Alexander Henry Higginson, MFH Middlesex Hunt, insisted that there was no such thing as an “American” breed, and that if there were, British foxhounds were still superior. A challenge was proposed. Smith was to gather hounds, Higginson would do the same and the packs would duke it out “for love, money, or marbles”, according to Higginson. The goal was simple: the pack that best caught foxes would be the winner. These Massachusetts Masters of Foxhounds decided that Middleburg, Virginia, would be the battleground on which the Great Hound Match would take place, and November 1 would be the first day of reckoning.

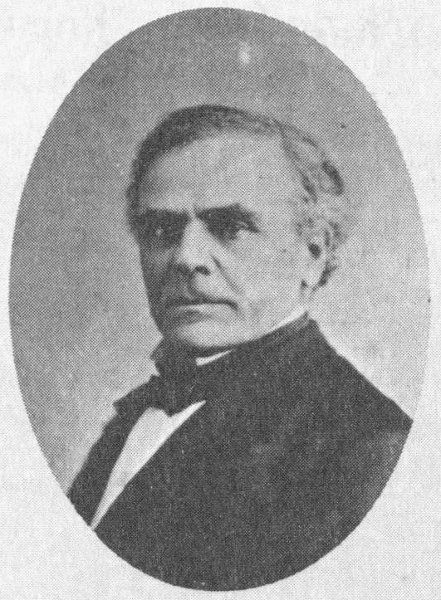

The Middleburg and Upperville areas were used to being contested territory. During the Civil War, the Virginia Piedmont Heritage Area was a borderland where armies skirmished and partisan rangers prowled. Most residents had at least one family member who had drawn arms in support of the Confederacy barely a generation ago. But newly arrived Northerners found they had a stake in history of the area too. On July 17, 1863 during the Battle of Aldie, Major Henry Lee Higginson, 1st Massachusetts cavalry, was knocked from the saddle, slashed with a saber, and shot twice. The elder Higginson survived the ordeal to become a successful broker, founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and sometime advisor to President Woodrow Wilson. Forty-two years after Higginson’s wounding at Aldie, his son Alexander Henry Higginson returned for a friendly competition in what used to be dangerous rebel territory.

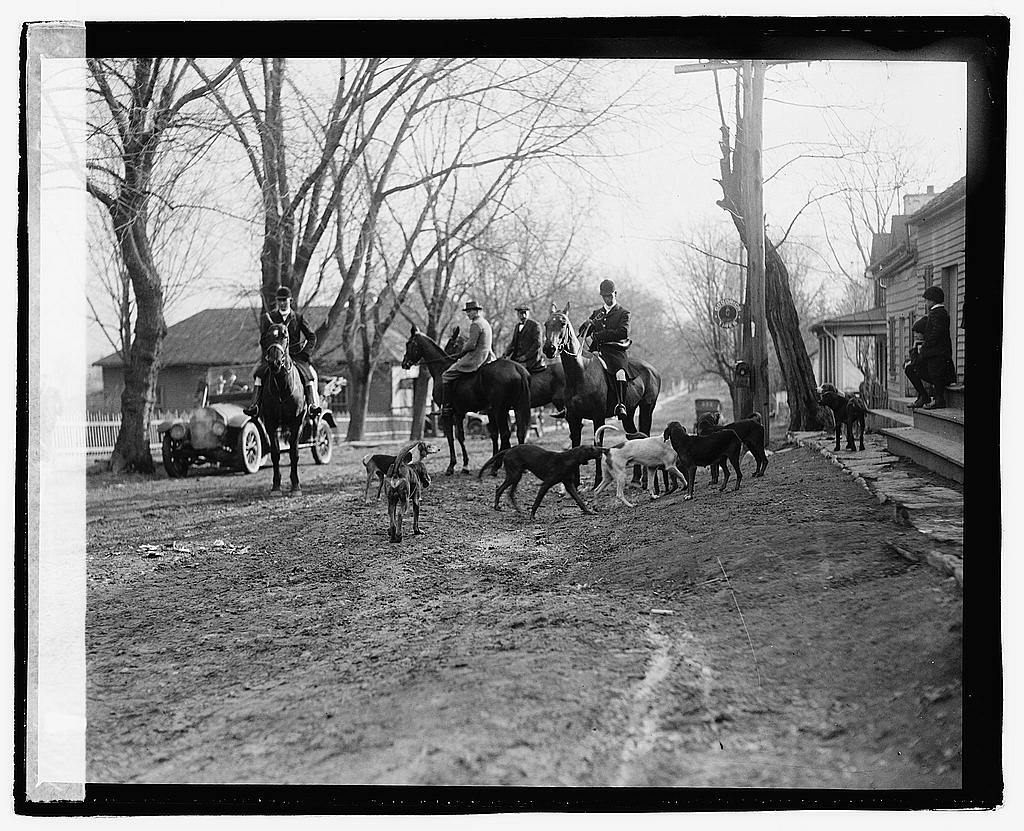

It was no surprise that the Loudoun Valley was chosen as the site for the Great Hound Match. Foxhunting had taken place in the area for nearly 150 years, and it was home to the United States’ oldest hunt club, the Piedmont Fox Hounds, founded in 1840 by Col. Richard Henry Dulany. In fact, the first day’s hunt began at the Colonel’s home, Welbourne, and was dedicated to the 85-year-old hunt progenitor. Dulany’s nephew, Henry Rozier Dulany, Jr., hosted Harry Worcester Smith and the Grafton hounds at Oakley near Upperville. Throughout the Great Hound Match, the field was dotted with equestrians from home and abroad, indeed, participants from 26 hunts joined in on the fun, including one hunt each from Canada, England, and Ireland. Northern Virginia’s rolling hills and rural pastures were (and still are) strikingly similar to traditional hunt country in Leicestershire, England, but the bucolic setting belies surprisingly deep creeks and steep cliffs. It is exactly the right setting for a grand drama on horseback, and that’s just what unfolded in November of 1905 as riders, whippers-in, hounds, reporters, grooms, and over 100 horses descended on the little train station in The Plains.

Far from the glitzy hotels and sparkling nightlife of New York City, Boston, and Washington, D.C., visiting equestrians hacked back and forth to Hound Match meets on dirt roads often mired in mud and farm traffic. Higginson’s British hounds from the Middlesex Hunt proved to be most popular during the Match, often drawing a field of 50 or more. Onlookers praised the foreign-born hounds’ cohesiveness, and while the hounds traveled fast, nearly everyone could keep up. Higginson was wont to meet in Middleburg and cast his hounds north of town towards the Fred Farm or at Lemmon’s Bottom just across the Goose Creek Bridge. In comparison, Harry Worcester Smith’s Grafton hounds often met at Oakley but would then gallop across the territory, from Upperville to Unison to Oatlands and back in one morning. On November 9th they met at Zulla and were headed to The Plains when the Grafton hounds ran head-first into the Orange County Hounds, who were out that morning with MFH John Townsend. The OCH was founded in Goshen NY in 1900 and only started hunting in Virginia in 1903. It was only a matter of time before all the Northerners started bumping into each other! Throughout the Match, the Grafton hounds went fast. A field that might start with 20-30 riders sometimes ended with barely a third of that number, and twice the hounds were separated from Smith and had to be rounded up hours later. Among the stalwart hunters who managed to keep up with the hounds were a handful of young riders, and usually a Mrs. Tom Peirce from Boston who rode aside. Flocks of locals followed the match on horseback, hilltopping at key vantage points to see the hunt field surge past in pursuit of the wily Reynard. While hunting near the Fletcher farm, Smith called out to a rider who was trampling through a farmer’s field of winter wheat. Smith demanded that the “son-of-a-bitch” stop destroying the delicate crop, to which the rider responded it was his wheat and he’d ride over it if he pleased.

The Piedmont landscape took a toll on even the most experienced riders. Frederick Okie of Piedmont Stock Farm nearly drowned in Pantherskin creek when he and his horse stumbled into a deep pool while chasing after the Middlesex hounds. That same day Harry Worcester Smith managed to break his foot and had to be cut out of his riding boot by Upperville physician Charles Rinker. Julian Ingersoll Chamberlain, who served in the New York cavalry during the Spanish American War, was not the only rider to go head over bridle while jumping over stone and barbed wire fencing. And the risks were not only physical. Higginson and a large number of his followers were arrested by Fauquier resident Amos Payne for trespassing in a wheat field. Payne insisted that all he wanted was a promise that the trespass wouldn’t be repeated, but the magistrate got involved and the situation was only cleared up with the intervention of Richard Henry Dulany, who didn’t want to jeopardize the area’s reputation to visitors.

The Great Hound Match lasted from November 1-14, with either the Middlesex or Grafton hounds running every single day except Sundays. Despite many chased foxes, no wild foxes were killed during the Match, leading some to speculate that it would result in a draw. However, in the end it was decided that Smith’s American hounds had performed better overall. Higginson accepted defeat with grace, and even his most ardent supporters admitted that they were impressed by the performance of the longer-legged contestants. Though the match was over, both Higginson and Smith had long careers in foxhunting ahead of them. The camaraderie inspired by the Match led to the formation of the Masters of Foxhounds Association of North America in 1907 with – who else?- Harry Worcester Smith as its first President. Alexander Henry Higginson was next to serve at the helm. Today MFHA headquarters are in Middleburg, Virginia. While hunt territory across the United States has been disappearing since the 1950’s due to suburban sprawl and new pastimes, open landscape and preservation have kept the sport alive in Virginia. The Old Dominion is still host to 24 active hunts, seven of which are in the Virginia Piedmont Heritage Area.

Special thanks to Erica Libhart, Mars Technical Services Librarian at the National Sporting Library & Museum, for access to the Harry Worcester Smith archive. For a thorough retelling of the Great Hound Match of 1905, check out Martha Wolfe’s book on the subject. For more about Harry Worcester Smith and his prodigious archives, make a research appointment with the National Sporting Library & Museum.